The Charm Of The Capital; Love Letter To Dilli

By Khushi Jain

To my muse, my magic and my mohabbat

We are stranded on different islands. There is an ocean separating us, pregnant with compulsions, rules and the necessities of time. It is also the ocean connecting us. Every evening, I fold a paper boat and leave it adrift and I whisper a prayer and send it to the skies, with the tireless optimism, that it will dock on your shore and the tides will reiterate the hymns to you.

You’re lonelier than I am and your loneliness is quite unlike mine. Life has been sucked out of you. Literally. I can see the analogy of a qabr forming in my head. You are holding bodies within you, bodies bereft of consciousness and animation, and haunting souls crying in exasperation at the dullness of their current existence. Life has been sucked out of you, and strangely, into you.

It seems like my origami is not reaching you. Perhaps it is to lessen this loneliness that I have been writing.

Most of my letters aren’t even addressed to you.

I wrote to that neighbour last week, who was a doctor on night shifts. She would come early morning to pick up her keys and late at night to drop them off again. I never saw her, at least not properly. She only stayed for two months.

I wrote to the man who sells books outside the Vishwavidyalaya metro station. He would set up his makeshift shop with the skills of an artist, somehow managing to display a hundred books on a slab of wood balancing on bricks and cement blocks. He would spend evenings sipping chai, a courtesy of the old lady from the stand right next to him, and eagerly fishing out titles from his big jute bag. It had become a ritual for me to stop by the books every day. I seldom picked any but my eyes would graze the spine of each. I bought a Penguin Vintage edition of Hamlet from him once and from that day forth, every time he saw me he’d tell me about the new Shakespeare book he had found.

I wrote to the rikshawallas sweltering around the stairs of every metro station. They would erupt in a volatile cacophony of rates and destinations whenever a customer would walk out the station. And with the same suddenness, they would quiet down, returning to lounging in the back seats of their rickshaws wearing torn baniyans and a headband that also served as a dusting cloth.

I wrote to the woman sitting on the floor of the Janpath Market, in between shops attempting to sell the idea of India. Her India was limited. Her daughter, her grandson, the torn and patchy quilt she sat on, the meal she might get to eat today, and silver jhumkas. Her blue board was covered with a tightly stretched velvet with punctured holes. Her jhumkas were universal – girls wore them to college, women to work, tourists to whichever country they came from, and even beggars to cars on red lights. Her India was a limit.

Last night I wrote to my best friend. I missed her a little too much. I just wanted to hold her in my arms and listen to her words forever. And that’s funny because I barely even saw her when things were normal. We owed all our dates to Ayushmaan Khurrana for only the release of his films brought us together. But this time, even that didn’t work. His film released online. But I didn’t need to constantly be with her to love her. Last night, I needed her to love me.

Today, I am writing to you.

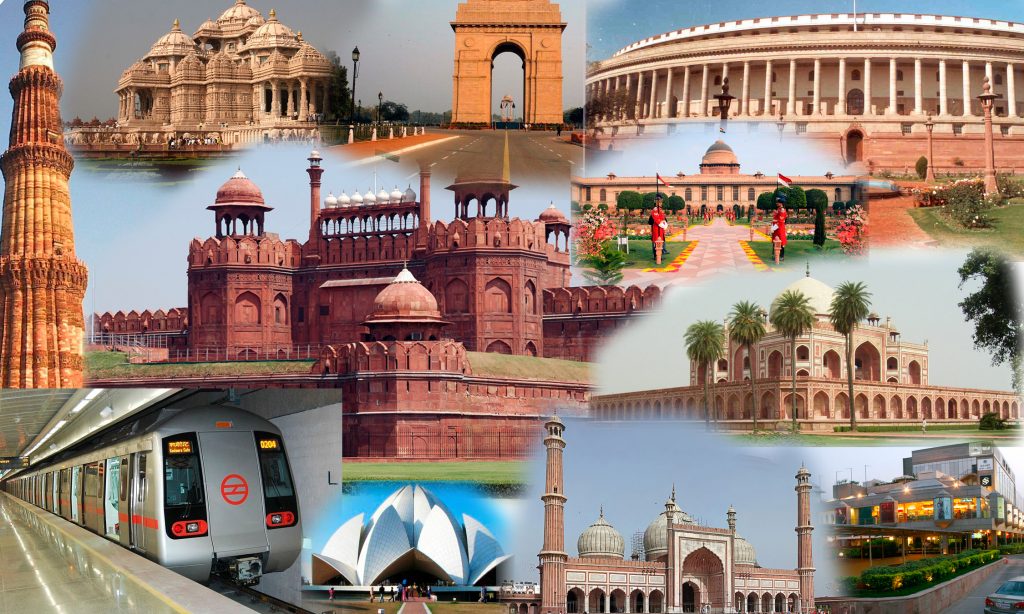

I will forfeit, be a cliché and say I miss you. I miss the fragrance of the honey frangipanis perfuming the Humayun’s Tomb. I miss the aroma of the adrak aur elaichivali chai curling out of earthen cups, mingling with raindrops at the countless tapris. The doorbell of my house reminds me of the darwaaze bayeen aur khulenge, kripyasaavdhani se utreinof the steel grey metros. My fingers ache for the rough red-sand-stones of the Khirki Masjid and my tongue craves that India Gate-valivanilla ice-cream wrapped in an evening of blushing orange sunsets.

But more than anything, I miss your spirit. You’d rise before the world, waking up the mynahs and koyals with you. The mornings would be abuzz with boiling water, wheat waiting to be kneaded and the smack of the newspaper hitting the iron gate. You’d groggily read the headlines with a Parle-G biscuit in between your fingers. You’d haggle with the sabziwallah for tomatoes. I’d breathe you in through the concoction of the pink blooms of my verandah and the blue skies of Delhi mornings. Afternoons meant a hasty lunch for both you me, I juggled lectures, notes and assignments with a mere twenty-minute lunch break full of society meetings.

You shared rajma chawal with people sitting cross-legged on rugged grass, eating out of steel tiffins on newspapers. A little later, while I took the metro back home, you feasted on a redundant TV serial about a girl, her mother-in-law and some distraught cousin trying to create complications, and a house snoring in its siesta. Evenings were undoubtedly the best part. You would compel me to take you out on a date. Sometimes it was a stroll in NGMA and sometimes we’d just sit, moving slightly to and fro on swings, too lazy to go higher. Dinner was more or less a family affair, a family without ma. She would eat afterward. Most nights, barring a few rare ones, you’d call the moon to lull me to sleep, ending my day perfectly. Then you’d take the moon out on a date. I have wondered so many times, where you took it, what you both did, did it end in a kiss?

But you’re miserly when it comes to words, you don’t talk enough to share even a little with me. Yet you’re not quiet. You tear the sky when you’re angry and jam the roads with honking cars when irritated, when you smile, the music of a little mynah plays on my ear drums and your joy finds ecstasy in the qawwalis of Nizamuddin’s Dargah.

I have never heard you cry. A few days back, it was silently drizzling. Droplets rand down the stubborn walls of the Red Fort. Water pooled in alcoves of concrete all over the city. Every flower and leaf shed a tear. Despondent grey clouds washed the colonial columns of Connaught Place wet. I have seen you cry. It lasted seven minutes and forty seconds and culminated in soggy identities and the birth of twin rainbows. What a tragedy.

You’re a dream for thousands, those who don’t know you at all, and those who know you too well. You’re the dream I wake up to every morning. I don’t know when this love story began, or if it even is a love story. I am going to call it a one-sided, unrequited romance. How else do you love one who so many others are already in lovewith. It’s a curse, a doomed ishq.

And yet you do, every day, every time. Can love become a routine yet in its familiar essence hold an originality of experience? Can it become a poem you know by heart yet have to read it each time you try to recite?

With the hope that this reaches you

And you drizzle again

Smog and dust mix with the air in New Delhi.

I buy jasmine for her hair in New Delhi.

People come from everywhere to this city;

all are welcomed with a stare in New Delhi.

The finest things in life don’t come without danger.

Eat the street food, if you dare, in New Delhi.

We push in line and fight all day for each rupee.

Can you remember what is fair in New Delhi?

There is nothing you can’t find in our markets.

Socks and dreams sell by the pair in New Delhi.

So many families on the street through the winter;

Sometimes good men forget to care in New Delhi.

My friends ask, Michael, why’d you leave your own country?

I found jasmine for her here, in New Delhi.

Michael Creighton