“Optimism, where it is not just the thoughtless talk of someone with only words in his flat head, strikes me as not only absurd, but even a truly wicked way of thinking, a bitter mockery of the unspeakable sufferings of humanity.”

As someone whose lived experience of adolescence was entirely an essay in woe-is-me sighing, I have always loved this quotation from Arthur Schopenhauer almost as much as I abhor optimism, positivity, and good morning messages. (If my relatives see this, please know that I am joking.) So it should come as no big surprise that as I became internet-savvy, I quickly developed some very intense dislikes.

Chief among them is manifestation. It is, quite categorically, my bête noire. It gives me the ick. It makes me deeply uncomfortable. It arouses my deepest suspicions.

For those who aren’t familiar with the concept, manifestation is all about bringing good things into your life through the power of positive thinking, affirmations, visualising outcomes really hard, and so on. And like all good things, it comes in an attractive package — in this instance, the internet version of spirituality.

I was never quite able to put my finger on why manifestation discomfited me so much until recently. It took some gut-wrenching soul-searching (and self-compassion) to convince myself that I am not merely vindictive when it comes to these matters. On the contrary, I was just being tremulously indignant and justice-sensitive. Anyway, I have since devoted myself, in my newfound good faith, to assembling a stockpile of well-thought-out arguments that help me make sense of my position. And the rest of this article, dear reader, is the modest fruit of these labours.

See, and Ye Shall Find

Being a tardy reader, I have an embarrassingly inordinate fondness for picture books. Perhaps one of the more sophisticated, cocktail-party-material pieces of this persuasion I have had the pleasure of perusing is Ways of Seeing, a collection of essays by the British art critic John Berger. (There is also a lovely BBC documentary of the same name, to which it was meant to serve as an accompaniment.)

Its premise — and opening sentence — is exceedingly simple.

Seeing comes before words.

The primacy and potency of the visual over the verbal, and pretty much everything else. (Cue visualisation!)

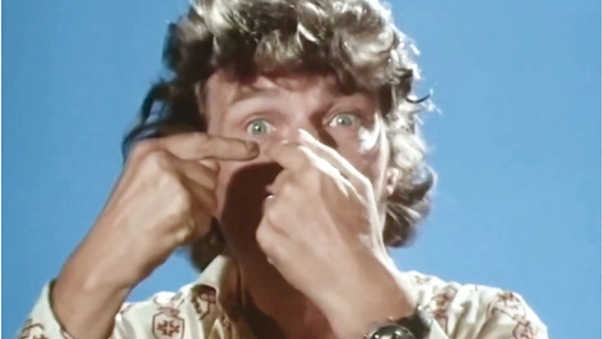

John Berger, “Ways of Seeing”, 1972, still.

But seeing itself is far from an innocuous affair; it is dogged by assumptions and attitudes. (The corollary is that images can be powerful vehicles of ideology.) It is these particular ways of seeing that Berger contextualises and critiques.

The seventh and last essay of his work engages with the subject of modern advertising, or publicity. I bring this up, because I shall eventually show that manifestation is publicity’s luck-mongering illegitimus.

Though written during the heyday of billboard advertising, way back in 1972, Berger’s critique of publicity images is just as applicable to a present of media saturation. Just consider how much (or how little) has changed since he made this statement.

“In no other form of society in history has there been such a concentration of images, such a density of visual messages.”

A digitally manipulated image of Times Square seamlessly combining elements of more than 20 photographs slicing across a century. (Carles Marsal, “Timescape”, 2016)

I shall now try to reproduce Berger’s argument. I quote liberally along the way, if only out of deference to the facility of the original.

Publicity is at once an evanescent and enduring phenomenon. We are constantly bombarded by its images. Of course, each individual image is momentary and its action on the imagination is equally fleeting. Collectively, however, these images are incredibly, incredibly effective. And that is without tipping our tinfoil hats to the subliminal messengers. So far, these are facts of experience, but they beg the question: whence comest this diabolical power of persuasion?

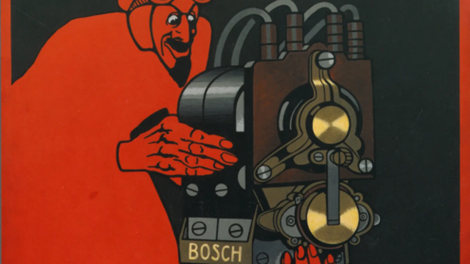

The Bosch Red Devil. Whence comest thou?

Berger’s response lies in a series of closely interconnected claims.

For starters, a lesson from Sales 101: whatever you are selling, you do not sell the product. Publicity executes this at the grandest scale possible by selling the “spectator-buyer” a version of themselves they could be if they come to possess something more — a version, moreover, that they would envy in their present state.

This is also why the individual publicity image, which sells a particular product, is feeble by itself, since it is not that which is being sold. In fact, it would defeat the cause of publicity to depict in altogether convincing terms “the real object of pleasure” — it would only remind the consumer how far they are from actually enjoying it. “Publicity is never a celebration of a pleasure-in-itself. Publicity is always about the future buyer.”

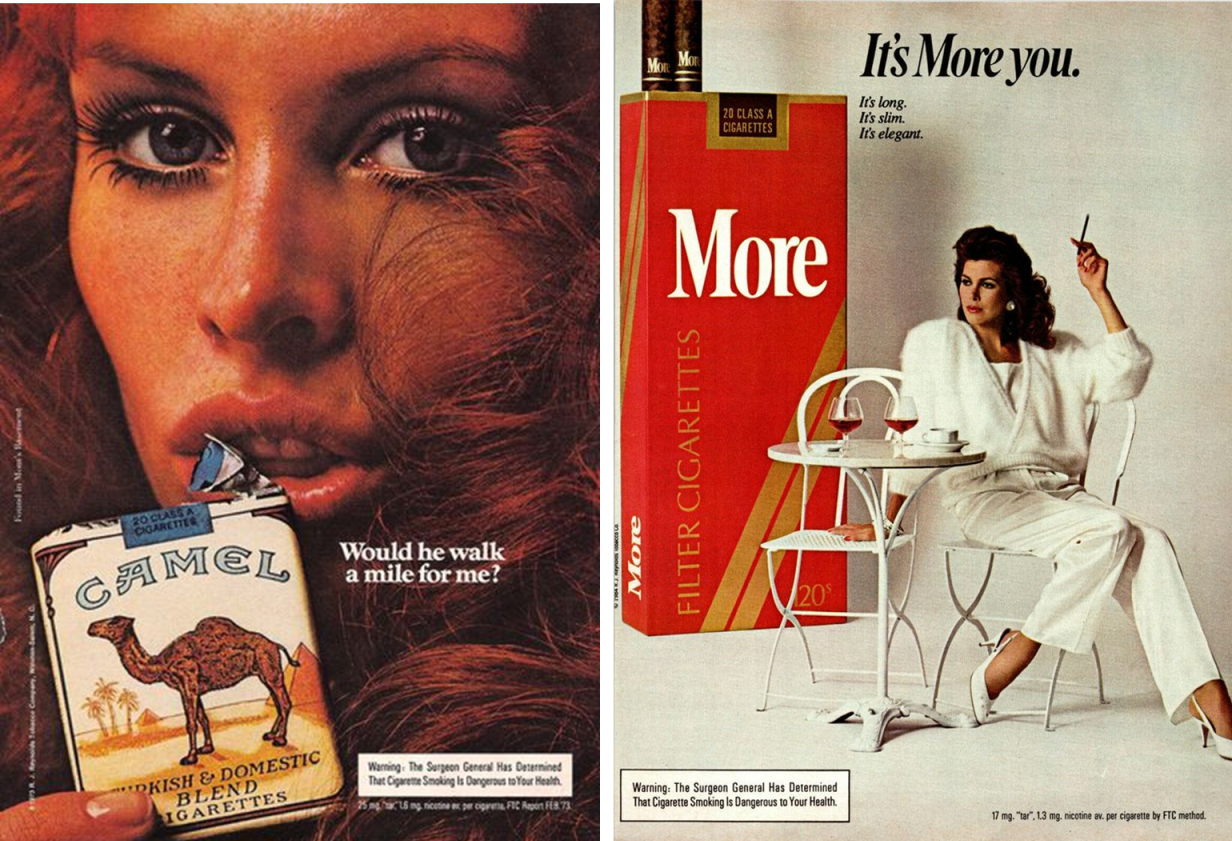

Ich bin du. Smoke and mirrors, or the idiom of publicity.

“The publicity image steals her love of herself as she is, and offers it back to her for the price of the product,” as Berger eloquently puts it.

The reader may notice that the snares are laid in the future; the bait dangles over the immediate present. And the love promised, and the fulfilment it would supposedly beget, are of a very specific kind. It is to Berger’s credit that he correctly identifies it as glamour, which he defines as the happiness of being envied by others.

The power of glamour derives from happiness; its sustenance, from envy.

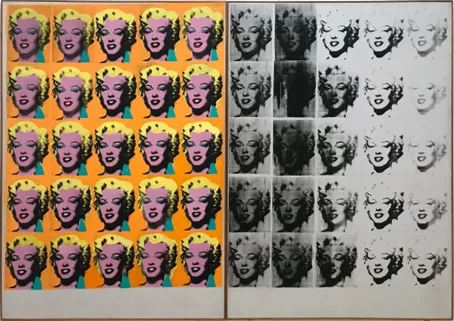

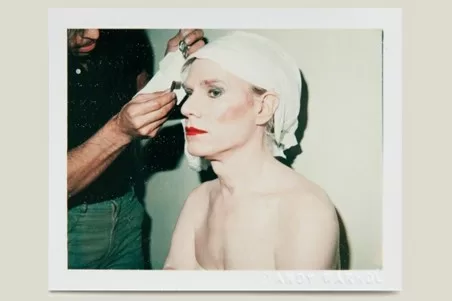

Envy is the sincerest form of flattery. (Left: Andy Warhol, “Marilyn Diptych”, 1962 | Right: Andy Warhol, “Andy in Drag Having Makeup Done”, 1981)

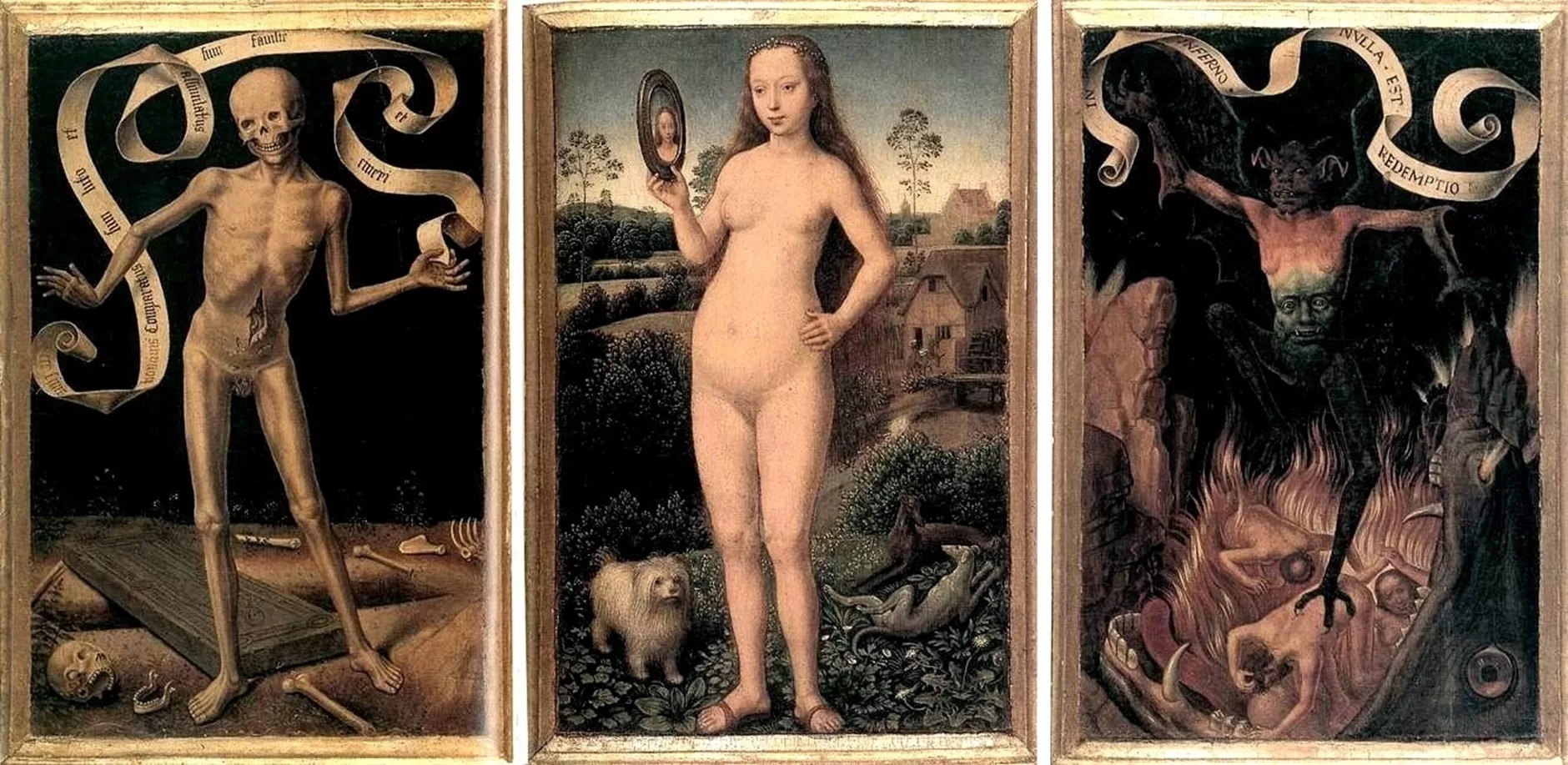

I wish to record a response at this juncture. Discussions of happiness, especially in the context of material possessions, have always been floating around. (One of the bones I initially had to pick with the concept of manifestation is the contradiction it presents of a decidedly materialistic message conveyed through a spurious spiritual medium.) Similarly, the conceits of self-love, stolen and resold by publicity, are reminiscent of the categories proposed by the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau: amour de soi (natural self-love) and amour-propre (vanity, as that which is moderated by social relations). This raises the question as to whether what has been described so far is much more than another instance of a folly inseparable from the human condition, treatable with a “tincture of philosophy”.

Hans Memling, “Triptych of Earhly Vanity and Divine Salvation” (front), c. 1485

But the spirit of Berger’s work is radical because it scrutinises the effect of images in the context of their historical conditions (as against the traditional, ahistorical practice of interpretation prevalent in art criticism). Reading him, one comes to realise that the onus of a systemic failure cannot fall on any one person caught in the machinery. (tl;dr: We live in a society.)

I found this digression necessary to reinforce what Berger has to say about glamour, namely, that it is a modern invention, manufactured by publicity, which in turn is “the culture of the consumer society” to which it sells, sells, sells.

Further, “the purpose of publicity is to make the spectator marginally dissatisfied with his present (my emphasis) way of life. Not with the way of life of society, but with his own within it.” A very telling remark.

The dissatisfaction Berger refers to is the anxiety of the “spectator-buyer”, who is made to feel that they will be happy and loveable, desirable and sufficient, a somebody instead of a nobody, by virtue of consumerist attainments. But there is of course always something left to desire.

Still from The Silence of The Lambs (1991), exchange between FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) and Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Sir Anthony Hopkins) about Marcus Aurelius, first principles, and criminal profiling.

Publicity is endlessly tantalising, and the ideal future of which it speaks is always just out of hand.

Berger’s answer as to how publicity nevertheless maintains its credibility is delightfully astute: “its essential application is not to reality but to daydreams.”

We have reached the crux of his argument. “The gap between what publicity actually offers and the future it promises, corresponds with the gap between what the spectator-buyer feels himself to be and what he would like to be.” These “glamorous day-dreams” of the “spectator-buyer” are the fantasies of the powerless where “the passive worker becomes the active consumer.” They reproduce the inherent contradiction of a society that recognises the individual pursuit of happiness but reserves the opportunities to realise it for a select few; such a society breeds “personal social envy” as long as it exists, so much so that within the same person, “the working self envies the consuming self.”

Berger’s ultimate conclusion is that “publicity is the life of this culture […] and at the same time publicity is its dream.”

Idea for a mad ad: A reality where publicity is literally the dream of our culture. (DAVID The Agency / Miami + Burger King / Miami, “The Nightmare King”, 2019)

I suspect that Berger’s critique can be extended to manifestation. After all, it follows the gnarly poetics of publicity to a tee: the optics, an essentially avidusque-futuri inclination, a la-di-da day-dream-like quality, the quiet elision of the present and its labour and its discontents, and the inevitable culmination in a grand and enviable personal vision of glamour (or more modestly, happiness or desirability or love) acquired through consumption.

Romantic relationships are a very common object of manifestation. Though it is not necessarily “material”, is love really contrary to envy? (Petra Cortright, “How to Download A Boyfriend”)

Of course, there is the matter of the spiritual register manifestation adopts, and the affirmation/empowerment harangue that is its typical bedfellow. As for the latter, it is entirely consistent with the powerlessness of the spectator-dreamer-buyer, which it is protocol to palliate. Regarding the former, I provisionally cite Berger again, who says that the publicity images of his time quoted past works of art because they simultaneously (and ambiguously) denoted “wealth and spirituality.” This is overtly the case with manifestation.

In some sense at least, manifestation is then the progeny of publicity. The only difference is that no product or advertisement intervenes; the ideal version of yourself — the completed image of publicity — now apparently springs from within. The dreams once occasioned by publicity images are now directly accessed by the individual in their most intimate form.

Manifestation is publicity naturalised, introjected, and regurgitated. A sort of post-publicity, if you will. It is the way of life to publicity’s way of seeing.

Father John Culkin: We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us. (Sir Edward Burne-Jones, “Pygmalion and Galatea II: The Hand Refrains”, 1878)

Before I proceed, I would like to exhaust my stock of Bergerian quotes and references.

“The entire world becomes a setting for the fulfilment of publicity’s promise of the good life. […] And because everywhere is imagined as offering itself to us, everywhere is more or less the same.”

I wonder whether manifestation’s favoured entity-at-summons, the Universe, is any different from this homogenised everywhere.

Skits of Frenzy

The process of identity formation (and dissolution) is one of the essential features of capitalism. But do not take my word for it. Jonah Peretti was a twenty-something amateur philosopher in the 90’s, who, among other things, authored an essay called Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1996). A decade later, he co-founded Buzzfeed, where he has been CEO ever since. Anyhoo, I believe a paper that allegedly provided the theoretical foundations for the web’s favourite micro-identity-churning platform would be as good a springboard as any for this section of my inquiry. (Besides being more contemporary, it would also neatly take over from the previous section. Consider its epigraph: “This article demonstrates the psychological link between one-dimensionality and advertising.”)

To understand the influence of images, Peretti finds it necessary to take a deep dive into the psyche, courtesy of French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. The mirror stage is a famous concept encountered in his writings, and it is just what the name suggests.

Kunisada (attributed), “Mirror which Reveals a Portrait of the Actor Segawa Kikunojō V in the Role of a Courtesan”, 1823

According to Lacan, personal identity — the “I” or the “ego” — is never given, but it is formed.

When an infant initially recognises itself in a mirror, it tends to mistake itself for its reflection and identifies with it totally. It is by assuming this image that the process of ego formation begins.

(The boundedness of the image it sees also leads to the isolating realisation that it is but “one object among many” in the exterior world.)

😯☝️😐✊(Image from “Lilliput Lyrics … Edited by R. Brimley Johnson. Illustrated by Chas. Robinson”, 1898)

But what is a joyous, jubilant experience at first — the infant laughs and smiles at the reflection — changes when awareness dawns that the serene, unperturbed ideal image (the “Ideal-I”) is at variance with the infant’s own complex and turbulent inner experience. The “drama of primordial jealousy” ensues. The infant is alienated from its image, perceives it as another, and the love it once had for the “Ideal-I” is supplanted by jealousy, competition, and desire. (It is this ultimate linking of desire and otherness that leads the infant from the mirror stage into the world of social relations.)

In short, ego formation is the result of identification with and subsequent alienation from an “idealised (mis)representation”.

Capitalism gets consumers to re-enact this infantile drama ad infinitum. I am sure the reader will have noticed the parallels between the “Ideal-I” of psychoanalysis and the idealised image projected by publicity, and between primordial jealousy and social envy, by way of a common process of narcissistic identification followed by anxious alienation. A Lacanian ego formation underlies consumerism; it requires the consumer to commit through time to the idealised (mis)representation with which they identify, at least long enough to buy the product on sale. (It must therefore speak in the future tense.)

(Dance) Square One (Screengrab from Dance Dance Revolution Extreme 2)

At the same time, capitalism must sell quickly, and quicker than ever. On the one hand, this is done by making it easier to purchase products (online shopping) until you can literally buy on impulse. On the other hand, identities must be shed as quickly as they are formed, in order to expeditiously make way for newer identities (and the products they endorse). This is why publicity images are transmitted the way they are: through bombardment and bedlam, cacophony and chaos.

As part of MTV’s rebrand, the slogan “I want my MTV” was changed to “I am my MTV”. According to Peretti, MTV was one of the principal (because ubiquitous) agents of ego formation/dissolution in the 80’s and 90’s. (Maxi Borrego, “I Am My MTV”, 2016)

The content of the images is no longer as important as the “efficiency and rapidity with which they are circulated and consumed.” The rhythm of fragile ego formation and dissolution comes to coincide with the extreme pace at which these images appear and disappear, until the Lacanian cycle is foreshortened and accelerated to the theoretical limit of schizophrenia.

The state that precedes ego formation, in philosophical parlance, is the “schizophrenic” consciousness, where there is neither a persistent sense of personal identity nor a meaningful distinction between self and the world.

Hence, Peretti’s thesis that “capitalism needs schizophrenia, but it also needs egos” to sustain itself.

If we read schizophrenia to strictly represent the theoretical limit and terminus, then it is well and truly capitalism’s “exterminating angel”. (I personally favour this interpretation, though this is because I am a hopeless Francophile.) If, on the other hand, we read the schizophrenic consciousness as that which engages in a continual process of ego formation and dissolution, then it not only resembles but reproduces the logic of capitalism.

Jonah Peretti: The schizophrenic would make a terrible shopper. This is because he cannot commit to an identity through time. (Still from Aalavandhan (2001), in which Kamal Haasan plays a paranoid schizophrenic.)

The rest of Peretti’s article is devoted to evaluating movements that he believes embody “anti-capitalist” schizophrenic consciousnesses. I do not get into this because our focus is the hocus pocus of manifestation.

Manifestation presents a very classically Lacanian process of ego formation, so much so that it might seem incongruous with the simulated schizophrenia of late-stage capitalism. I can try to propose a tentative answer to this.

Strictly speaking, there are no intervening images when it comes to manifestation. Perhaps several accidental images (and also accidents, or “coincidences” — egregious examples are angel numbers, astrological events, and algorithmic suggestions — the world itself is factitiously interpreted in terms of manifestation’s framework, despite whatever they say about a broken clock) are appropriated by the image of the ideal self, which could well be protean enough to make such accommodations. (In the end, aren’t we all bundles of thought?) On the other hand, when the rhythm of reinforcement becomes as rapid as breathing (and as natural, according to at least one influencer out there), we must literally discover the non-self between breaths, thus engaging ourselves in a curiously Buddhist exercise.

Venturing further, I am tempted to borrow a concept from the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (D&G), whose magnum opus is the namesake of Peretti’s paper. They speak, among many other things, of a “miraculating machine”. The CliffsNotes version is that it is a body or surface that merely “records” something but deceptively appears afterward to have caused what was recorded. This puts the miracle in the miraculating machine, because it is unproductive, or sterile, by definition.

A crude analogy would be a paper containing a message written in invisible ink. Should the “recorded” message magically emerge from the paper (upon the inadvertent application of, say, heat), one could just mistake the paper to have caused the writing if they did not know better. (GIF by u/this__one on Reddit)

D&G provide the example of capital, which according to the Marxist construction, merely measures labour in terms of the value it creates (the value theory of labour); however, by a breed for barren metal, so to speak, capital apparently becomes the source of value. The miraculating machine is thus a fundamental part of the logic of capitalism, and I would not be surprised if it is replicated in the case of manifestation. The manufactured desires (especially, their instances) of the manifesting subject are a recording of the images wrought by a schizophren-ish publicity, but they are erroneously located within the innermost heart or soul of the manifester. But all this is speculation, and I owe it to the reader to return to terra firma.

Manifest Desire

An excellent article by Jesse Meadows at Sluggish traces the troubled lineage of manifestation as we currently know it. (If you love yourself a good Internet rabbit hole, feel free to visit the link and skip to the next section when you come back — but please do!) It is also the most convincing explanation I have found for its penchant for spirit-speak.

In their article, Meadows draws a straight line from manifestation through such notorious(…ly popular) self-help books as Rhonda Byrne’s The Secret (2006) and Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich (1937) all the way back to the commencement of the Anno Ford era. The mysterious connection? A conspiring, conniving lot we all know and love: the wealthy elite. It is not what you think, though.

Novus ordo seclorum. (Mark Wagner, “Mirror Mirror”, 2019)

In some way or the other, all the books, speakers, and leaders of Meadows’ secret history are exponents of the New Thought movement, whose central tenet is that the power of thinking can transform one’s lot in life. It started innocuously enough in the 19th century, when a self-proclaimed healer, Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, preached that one could heal the body with the mind. (The founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, was his patient and protege.) Soon, though, it became a quest to attract wealth that reached a peak with Hill’s Think and Grow Rich — a book born out of a secret imparted to him, as he narrates, by the industrialist Andrew Carnegie. Almost seventy years later, Byrne came out with her version of it, in print and on tape. Another contemporary figure, Esther Hicks, also had a few words to say about what she called the Law of Attraction.

What they all say, in so many different ways, roughly amounts to this: there is a spiritual entity or agent (the Universe, “Abraham’”, “the ether in which this little world floats” (this, well after the Michelson-Morley experiments and the theory of relativity), some quantum physical substance) which is responsive to your innermost thoughts, or the energies or frequencies thereof, and endows them with a physical form. Of course, they must be positive, passionate, and pellucid for this to happen. It is all you, and only you (reassuringly so!), at the threshold of a vista of vast connection.

This “esoteric” truth is what the crazy rich have guarded and gatekept for generations (ironically enough, until the age of mass publication — and dissemination) because it is all that separates them from John and Jane Q. Taxpayer. And their shibboleths, you guessed it, are visualisation, positivity, and . . .

Yabba Dabba Duh.

This is essentially the rhetoric of manifestation. And behind every great rhetoric stands ideology. Consider the arguments made on behalf of manifestation. The everyman is offered a key to wealth and convinced that it is tantamount to wealth itself. Those who already have it made because they understand this secret are either thus divinely entitled to their wealth by the authority of this knowledge, or depraved because they withhold it. But this is where it gets really weird. We cannot eat the rich; instead, we ought to swallow our feelings and take the high road, or “ascend”, as some would have it. Individual salvation is recommended by rule.

M’kay, Kim K.

Let us parse this. The self-help-seeker is usually an oppressed individual — a seductively socialist premise. This oppression is acknowledged and so are its perpetrators, but then the cause is falsified. It is not capitalism’s system of exploitation or mass economic inequalities, combatable by joint effort, but the effect of some arcane article of knowledge to which the seeker is as yet uninitiated. In fact, it is all that is lacking. The rich are exempted, because they are initiated and hence deserving. Once again, the responsibility falls squarely on the seeker’s shoulders (“it is in their hands”) for choosing to play truant at the sacred lesson.

By exhorting individuals to naïve navel-gazing, as is the practice of manifestation in essence, collective action is nipped at the bud.

To quote Carolina Fernandez, a scholar Jesse Meadows references, it “borrows socialist rhetoric to hail the individual as an oppressed member of society, and then instead of suggesting a revolution of the masses that serves to lift up all in the working class, suggests […] that entrepreneurialism […] is the answer to their oppression.”

Fernandez characterises entrepreneurialism, according to this rhetoric, as “individual socialism” — a contradiction in terms. Any genuine desire for change, besides, is deflected by an unconditional, but cleverly disguised, appeal to our more narcissistic impulses.

The reader might recollect my remark that publicity is symptomatic of a societal ill. But manifestation touts itself as the cure to this ill, founded on wishful thinking and bent on reinforcing the logic of late capitalism within the individual. And herein lies the correspondence of the macrocosm and the microcosm of which it speaks in such exalted terms.

Inner-router. (Bulaki, “The Equivalence of Self and Universe”, 1824)

I would like to briefly discuss a few more things (quite a few of which are present in Meadows’ article).

The rhetorical use of spirituality cozens those with liberal sympathies into investing in a fundamentally conservative ideology besides bolstering the beliefs of those who already buy into it. Because it preserves and extols capitalist principles, New Thought and manifestation have been championed by wildly successful industrialists and businessmen, going all the way back to Henry Ford (though the masses know you can’t have anything in Motor City). The emphasis on the individual (read, main character) builds upon the favourite myth and legend of capitalism — the self-made man and his story of rags to riches — one, that, moreover, is used to indict the masses who cannot extricate themselves from poverty.

Also, historically speaking, dire economic straits and New Thought type thinking seem to herald each other: to name a few, The Great Depression (Think and Grow Rich), The Great Recession (The Secret), and, most recently, the Millenial/Gen Z post-pandemic cost of living (“cozzie livs”) crises (social media manifestation). I am obliged to quote Meadows here by way of explanation; it is “because they (these messages) feel personally empowering at a time when the masses are grappling with terrifying economic precarity.”

The concept of ascension, that is, ascending the need for money, is paralleled in the social media version of the law of attraction. The Universe will give you what you want, but it will deprive you of what you need: a grim predicament of cosmic proportions for paupers anonymous. The corollary is that manifestation can only be afforded by those who are “marginally dissatisfied”, but not much worse. A counterpart of this concept of attraction is the “abundance mindset”, which is where the tone-deafness of social media manifestation really begins to show.

Finally, I must remark that the statement that goes, “the Universe is always working in my favour”, is a curiously straightforward confession of privilege, sans the guilt that it is savoir-vivre to feel in this very situation.

Work Itch

You wanna? (Britney Spears, “Work Work”, 2013, video still)

The Princess of Pop (Philosophy)’s bop begins with the Christmas list of every material girl. The look book for the music video is also to die for. But what I really love about Work, Work is that it has gotten me through countless hours of assignments and exam prep, being a genuine source of inspiration (the YouTube comment section testimonials will back me up on this). As fate and internet irony would have it though, it also served as my personal unlikely introduction to Marxist theory — and the final answer to my many misgivings about manifestation.

The meme that started it all.

The lyrical correspondences were key. Britney does not leave a thing to be desired when she tells us what to want. But where manifestation would go on to instruct us to, well, manifest, Ms. Spears delivers an anthemic message of authentic gumption: the word “work” appears a mere 49 times. When I had my epiphany (as one does) listening to these tireless iterations for the umpteenth time, I realised that manifestation maintains an uncomfortable silence about the reality of work and even seems intent to gloss over it at every turn. Here’s the conclusion I jumped to.

Manifestation undermines work; capitalism exploits labour.

One of the cornerstones of Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism, Das Kapital, is surplus value and the related labour theory of value (or the value theory of labour, depending on how you slice it, though Marx himself never used either term). He asks, like many economists before him, just how the capitalist mints profit from the sale of a commodity.

The answer, in its simplest form, is that even when the capitalist, who by definition owns the means of production, buys labour (which is a commodity under capitalism) and sells commodities at their “real” value, there is a discrepancy between the actual labour done by workers and the “socially necessary” labour required to secure the average worker’s livelihood, that is, their roti, kapda aur makaan. (The label “socially necessary” refers to the standard of living prevailing in a society, and also the skill of workers on average, and the “normal” conditions of production, used as a yardstick.)

Since labour is a commodity that workers sell at the price of their living wages, it is also valued and compensated according to this, and not the actual labour done. Then, the value obtained from the surplus of labour — surplus value — is the source of profit, which in turn expands as the proportion of surplus to socially necessary labour, usually measured in terms of working hours, increases. Marx formally calls it the “rate of surplus value” and also “the rate of exploitation”.

Richard Wolff: Capitalism Is Ripping You Off

Prof. Richard Wolff’s accessible yet polemical introduction to the theory of surplus value.

It is worth noting that in the real world, commodities sell not at their real values but at the “price of production”. Also, Marx specifically means exchange-value when he discusses value in the context of this theory; exchange-value refers to the value a commodity has on the market, without any reference to its utility (this would provide the use-value). Since the exchange-value is thus abstract and general, it accordingly reflects the abstract and general aspect of labour, that is, socially necessary labour. Finally, it goes without saying that the pursuit of profit is intrinsic to capitalism; that “production is merely production for capital.” The collective action of the working class is the sole solution to its ravages. (The reader might recall capitalism’s overeager emphasis on the individual in contrast.)

Anyway, Marx’s argument reveals certain fundamental characteristics of capitalism, primary among which are the necessary exploitation of labour and the alienation of the worker who sells themselves along with their labour. I claim that the late-capitalist subject presents curiously distorted replicas of these features.

. . . Comrade Britney Did It Again!

Hustlers and their grindset offer an illuminating example. The very idea of hustling reflects the remarkable fluidity of a labour which offers itself (again, as a commodity) on the market many times over and in so many versatile capacities. But beneath this, one may sense a dimly miserable awareness that compensation is invariably compensation according to “socially necessary labour”, utterly indifferent to the time and heart poured into the job. I elaborate. The hustler seeks many opportunities simultaneously because they would roughly multiply the same modest compensation over the same amount of time (since only a portion of it is necessary for any one gig), until this presents itself as a source of relative prosperity. Hence, also, the cynical disparagement of the 9 to 5, when it should really foster sympathy. This is also why the grindset, which preaches the maximum utilisation of time, can never be divorced from hustling; after all, what is the use of investing in any one place that never truly pays you according to the actual work or time you put in? In fact, hustling culture very simply concedes the impossibility of this situation. The alienation of the hustler also becomes apparent in the fact that a philosophy ordinarily conducive to passionate endeavour is bent to a less worthy end. But what is really concerning is that, somewhere, somehow, the core belief that the hustler holds on to is lamentably anachronistic, even Ricardianly so: that time is money, pain is gain.

Glamorising the grind. (Pawel Jaszczuk, “High Fashion”, 2019.)

Zizek Challenges Peterson: “Set Your House in Order Before You Change the World?”

Excerpt from the Peterson–Žižek debate, officially titled Happiness: Capitalism vs. Marxism. Žižek’s critique of grind guru Jordan Peterson’s sixth commandment — set your house in perfect order before you criticise the world — is that your room is a mess because society is a mess. This was one of the springboards for my article, since apparently innocuous advice may, unbeknownst to itself, be laden with ideological presumptions.

Thus, the grindset presents a somewhat extreme instance of capitalistic conditions embedded in the subject, and specifically distilled into the issue of labour. It is replete with contradictions; while it looks at some of capitalism’s harshest realities straight in the eye, it also turns a blind eye to other aspects in order to survive. Manifestation, on the other hand, under its air of whimsy and saccharine good conscience, is an outright endorsement of capitalism, especially in its relation to labour.

Meadows’ article has a very provocative conclusion. They bring up the “Amazon Delivery Method” of manifesting, which exhorts us to believe that the Universe will grant our wishes just as certainly as the Amazon supply chain ensures a delivery will reach us. Then they point out how blissfully ignorant this is of the reality of the supply chain, where warehouse workers are mercilessly exploited to the point that they have to pee in bottles. The desires manifestation breeds almost invariably rely on the exploitation of someone else for their fulfilment.

But what is equally pernicious is that labour itself is stripped of its dignity by manifestation. Let us briefly indulge in a thought experiment.

Imagine an indefatigable worker who has laboured for the better part of a decade without having quite reached where they initially envisioned themself to be. Though this could be for any number of reasons, excepting the sin of sloth, is it really inconceivable that a practitioner of manifestation would ascribe this poor wretch’s lack of success to not having manifested hard enough? And that this would be executed without a holier-than-thou attitude? Here, the importance of being earnest is hopelessly misplaced.

I contend that the situation I have described is often sufficiently close to reality for the following reasons. Firstly, a relative position of privilege is the precondition for manifestation, as is evident from the attitudes the latter adopts. Secondly, the devaluation of labour is internalised, since it is no longer considered the necessary and sufficient condition for any level of success or enjoyment; manifestation is at least equally important to these things, though it is infinitely more facile. This is an exacerbation of the paradoxical “split personality” Berger describes as occurring under publicity: the passive worker and active dreamer. Further, a certain sheltering from the reality of work, accompanied by an undermining of its importance, is what I believe imparts the feel-good factor to manifestation, beyond or beneath the positivity it swaddles itself in. The alienation of the capitalist subject from labour is complete by rendering work itself superfluous. Any remnants of the anxiety Berger describes as fundamental to publicity are supplanted by the supply-chain certainty of getting there, until we have already arrived in the promised land of pure pleasure, heavenly felicity, and blinding joy.

Samo Tomšič, in The Capitalist Unconscious: Marx and Lacan: Capitalism is not perversion, but it demands perversion from its subjects. In other words, capitalism demands that the subjects enjoy exploitation and thereby abandon their position as subjects. (Image by Caspar Benson)

But I come back to the message of Work, Work. (As a song, it is meant to be enjoyed. It’s not that deep. I only talk about it as something edifying because it became my anthem along the way, and because the mind works in mysterious ways.) It is impossible not to desire something in today’s world. Even the monk is glamorous, if only because he sold his Ferrari. While the lyrics of Work, Work fully acknowledge this reality, they never fail to remind us that honest work and self-reliance is the way to go. That song is the middle path I choose between manifestation and the grindset. And I honestly love it for that so much, stanning aside, because it was a godsend at a time when the Internet would not quit pummelling me with messages that were just not meant for me.

I must record that I am inclined to sympathise with those who use manifestation as a crutch or a placebo in times of genuine hardship; though it is but a counterfeit of hope, and one deeply flawed at that, as I have endeavoured to show, society at large is to be blamed for this, and not the individual. (A friend whom I admire for his indomitable work ethic holds that the road to hell is paved with good intentions.) However, I do find its greedy consumerist cousin to belie an unjustified complacency and wilful ignorance in the face of the complex realities of late-stage capitalism; it flaunts some of its most outrageous tendencies under a fancy veil. And while work may no longer be worship due to our tragic alienation from it — and each other — I believe we should do our best to reclaim our sense of work, and solidarity to boot.

Declaration of Interest

I would urge my reader to scrutinise my argument for themselves, and also to take it with a grain of salt. In the end, I am frankly too much of a dilettante to be a Marxist or anything else. Besides, every successful ideology contains some kernel of truth. Finally, a good part of the reason I ventured to write this article stems from shamefully personal motives. All I will say is that I was born to be p(r)etty, but I am forced to philosophise.

In parting, I wish to observe that Internet discourse regarding manifestation and the grindset seems to be gendered for the most part, with the girls and the gays favouring the first camp while the men side with the latter. My two cents are that this state of affairs only serves to revive and reinforce traditional gender roles. I also lament that the adoption of manifestation by the queer community ever so slightly defuses their wonderful subversive potential for the same reason. I am slightly reluctant to explore this topic in greater detail, so I shall leave the reader to ponder over it. Until then, I wish you well.